Guardian of Royal Blood

A historical narrative following the journey of a Romanov Martyr’s relic - protected by a young Russian patriot & future Orthodox Bishop, who would survive wars, Talmudic revolution & exile.

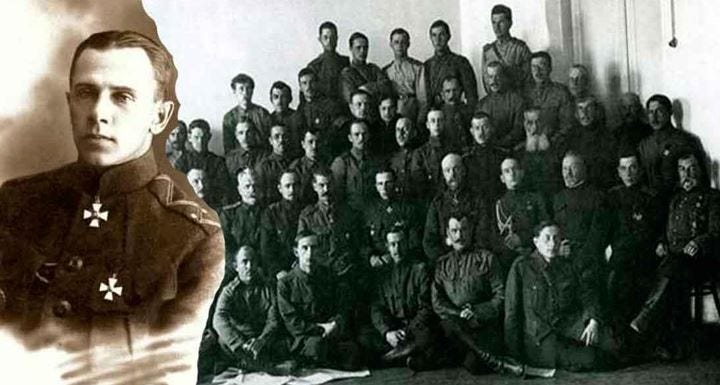

This is an important and unique historical account concerning one of the relics of the Royal Romanov Martyrs - how it was preserved and safeguarded by a Russian teenage boy who would soon become a veteran of the Civil War against the Bolsheviks, and later of the Second World War on the side of the Third Reich. His life, and the lives of those he encountered, were all marked in varying degrees by the tragic aftermath of the Russian Revolution. The man himself would eventually devote himself fully to Christ, becoming a priest and, in time, a bishop of the Orthodox Church.

This is a translated, edited and amended version of Sergey Fomin’s “A Drop of Royal Blood” published in 2024.

25 July 1918, was the last day of the Red Bolshevik presence in Yekaterinburg.

The somber mood among the advancing White Russian forces was later conveyed in a poem by one of the participants, Lieutenant Arsenius Mitropolsky, better known by his literary pseudonym, Arseny Nesmelov:

"Why does the grey-mustached warrior weep?

In every heart there smolders the ash of countless fires.

In Yekaterinburg - bow your heads,

Our gentle Sovereign died a martyr’s death.Speech stills, every word falls silent,

In boundless horror our eyes are raised.

Brothers, it was like thunder,

A blow that never can be forgotten.A grey-mustached officer stepped forward.

He raised his hands toward the heavens and said to us:

“Yes, the Tsar is gone - but Russia lives,

Our homeland, Russia, remains.”

The same feelings of were experienced by John Petrov, a young cadet of the Kazan Military School. Despite being underage, John volunteered to be part of the Russo-Czech Ural Group under White Army Colonel Sergey Voitsekhovsky, along with many of his class-mates who refused to see Orthodox Russia fall to Talmudic Bolshevism without a fight.

This Russo-Czech unit was the first to enter the city and was thus renamed the ‘Yekaterinburg Regiment’.

The hero of our story, John Nikolaevich Petrov (anglicized form of Ivan, Ioann) was born on 24 December 1902, in Yelabuga, Vyatka Province, into an officer’s family.

He studied up to the 7th grade in school, after which he entered the Kazan Military School. It was from there, at the age of 15, that he joined Colonel Sergey Voitsekhovsky’s detachment in the summer of 1918. The Russian Civil War was ongoing for over 7 months at that point.

Voitsekhovsky’s grandnephew, Sergey Tilly, recalled:

“...A few days before that fateful night, Czech scouts managed to slip into the city, which was surrounded by the Legionnaires. Moreover, they succeeded in delivering an ultimatum from Voitsekhovsky to the Ural communist leaders. Its meaning was simple: release the Tsar and his Family, and I guarantee you a safe exit from the encircled Yekaterinburg; otherwise, the city will be taken, and death for you is inevitable. Alas! It was not to be. The city was taken, but the leaders and participants in the execution managed to slip away, leaving rank-and-file Bolsheviks to face the consequences.”

General Mikhail Diterikhs, describing the first hours after the liberation of the city:

“The morning of July 25, great agitation spread among the officers who entered the city when it became known what condition the Ipatiev House was in, where the Imperial Family had been held. Everyone who was free from duty or guard assignments made their way to the house. Each person wanted to see the last refuge of the August Family; each wanted to take an active part in resolving the question that tormented everyone: Where are They?Some inspected the house, broke open nailed-shut doors; others rummaged through scattered belongings, trinkets, papers, scraps of paper; some scooped ashes out of the stoves and sifted through them; others ran through the garden and courtyard, peeking into every shed and basement. Everyone acted on their own, not trusting others, fearing each other, and striving to find some clue – some answer to the question that disturbed everyone. (…)

Aside from the officers, a large number of various people gathered at the Ipatiev House. There were ladies, local bourgeois, street boys, market women, and just idle townsfolk. Some were driven by serious intentions and genuine interest, others came out of mere curiosity or habit – to be wherever a crowd had gathered – and some came with a clear goal: to profit, to steal something and sell it.

While the officers and respectable visitors examined the house, inspected the rooms, made assumptions, shared impressions and various rumors – those who came ‘just because,’ and those with clear intent to plunder – took and carried off many abandoned items. Much of it later turned up at markets and junk stalls. Some people also took things as souvenirs.

In the afternoon, the garrison commander sent a military detachment. Everyone was removed from the house; the building and gates were locked and placed under guard. A strict order was given that no one was to be allowed in without special permission from the military authorities. (…)

…On the third day after the city was taken, officers attached to the staff of garrison commander Colonel Sherekhovsky began an investigation into the murder of the former Emperor. (…) On July 29, the investigation was given an official status by assigning it to Judicial Investigator for Major Cases, Nametkin, who had already been invited earlier by the military authorities to assist in the investigation.”

"On one of those days, the cadet John Petrov visited the Ipatiev House and ‘took for himself a piece of plaster that had the blood of the Royal Martyrs on it.’"

Other eyewitnesses also testified to these particles of the Royal relics in the form of blood splashes of the Martyrs from the basement of the Ipatiev House.

At the same time as John Petrov, the house was visited by a cadet of the Military Academy (which had been evacuated to the city), Guard Captain Dmitry Malinovsky (1893–1972), who was part of a group of officers striving to provide every possible assistance to the Imperial Family.

In his testimony to investigator Nicholas Sokolov on 18 June 1919, he stated that he had been to the Ipatiev House “about three times" (the first time on 2 August 1918, together with investigator Alexander Nametkin).

He observed that the floor in the room of death “showed signs of being scrubbed. On the walls of that room, on the wallpaper, I saw blood splashes near the bullet holes.”

(The Case of the Murder of Emperor Nicholas II, His Family, and Their Entourage, Volume II, 2015, p. 80).

In September 1918, Professor Erich Dill (1890–1952) of Tomsk University was guided through the same room by the successor to investigator Alexander Nametkin - member of the Yekaterinburg District Court Ivan Sergeev (a baptized Jew):

“On the walls opposite the entrance and the only door, was a whole row of indentations made by bullets being extracted from the logs that formed the walls; the traces and nests of deeply embedded bullets were clearly visible, despite having been dug out with a knife. On the floor were several rectangular holes; parts of the floor had been sawn out, apparently to collect bloodstains for the investigation. In some places, blood splashes were still visible on the floor and walls. The bullet marks were at various heights on the wall - both above and below the shoulder level of an average-height person…”

(Sergey Fomin, “The Tsar’s Case” of N.A. Sokolov and “Le prince de l’ombre”, Vol. I, Moscow, 2021, p. 196).

In a photograph of the eastern wall of the semi-basement room, investigator Nicholas Sokolov specifically marked the stains and blood splashes found there.

Sokolov’s assistant and bodyguard, Captain Paul Bulygin wrote:

“Thirteen drops of this blood, placed in arsenic capsules, are among the material evidence in the investigative files (…)

They “have been carefully preserved to this day” (p. 94).

The Royal relic (a piece of plaster with the blood of the Martyrs), discovered in late July 1918 in the basement room of the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg, was preserved by John Petrov, who carried it with him throughout his difficult and dangerous life.

He was destined to live nearly seven more decades.