Ritual Regicide: The Martyrdom of the Romanovs - Part II

Part II of an extensive exploration into the truth, symbolism, and cosmic significance of the Ritual Regicide/Martyrdom of the Romanov Royal Family 👑🇷🇺☦️

As we continue our exploration of one of the most heinous crimes of the 20th century, we encourage readers to first consult the First Part of Ritual Regicide, released in April 2024. For a more comprehensive understanding of the events discussed in this article, we highly recommend reading The Romanov Royal Martyrs: What Silence Could Not Conceal. This book offers an in-depth context to the intricate case study presented here on WorldWarNow.

Since the time of the cross-bearing victory and the destruction of the ‘gates of hell,’ the union of human and devilish efforts towards murder - in other words, the cunning restoration of the demolished ‘gates of death’ with the trowel and compass of global Judeo-Masonry - has become the essence of the mystery of lawlessness operating in the world.

The ‘gates of hell’ or ‘gates of death’ (Psalm 9:13) are referred to in Holy Scripture as "the various tortures of martyrs, which usually led to their death. The highest and most significant of these tortures, of course, were those endured by our Savior Himself" (Euthymius Zigabenus, Commentary on the Psalms, Kiev, 1882, p. 56).

According to the teachings of the Holy Church, after the incarnation of Jesus Christ, the devil's dwelling place is the abyss, hell, the underworld. However, for some fallen spirits subordinate to the devil, referred to as the "powers of the air" (Ephesians 2:2) and the "spiritual hosts of wickedness in the heavenly places" (Ephesians 6:12), access remains open to a space called the lower or mental air. Nevertheless, even for these aerial demons, in order to remain in the sub-heavenly realm, they require a certain auxiliary means, or better said, a nurturing medium, which for them consists of the vapors and exudations from bloody sacrifices offered to them. These are the very sacrifices that demons especially need to remain in this dense air surrounding the earth, for their nourishment consists in the scent of the sacrifices (Origen, Exhortation to Martyrdom, St. Petersburg, 1897, p. 217).

"Such is the custom of demons," confirms St. John Chrysostom, "When humans offer them divine worship with the fragrance and smoke of blood, they, like bloodthirsty and insatiable dogs, remain in those places to feed and delight in (this fragrance and smoke). But when no one offers them such sacrifices, they disappear as if from hunger. As long as sacrifices are offered, as long as vile rituals are performed, demons are present and find enjoyment" (in the book by Bishop Ignatius Bryanchaninov, Ascetic Experiences, volume 3, p. 274).

The thirst for sacrificial blood urged demons to inspire bloody sacrifices in the ancient world. As Tertullian says: "They (the demons) recommend people to venerate the well-known gods so that they themselves may obtain food contained in the fat and blood of sacrifices offered before the statues of gods and their images..." (Origen, Exhortation to Martyrdom, p. 217-218).

And after the divine suffering of the Savior, which destroyed hell and established His kingdom on earth, bloodthirsty demons, having embodied themselves in the God-rejecting assembly of the Jews - this figurative swine herd - attempting to overthrow the throne of God through secret ritual murders.

If the bloodless sacrifice and the throne of the Roman emperors, the external bishops of the Church, sanctified to protect it from visible enemies - the staff and sword, two weapons of God, mystically and physically working to bind and restrain the devil -then the bloody demonic sacrifices are the loosening, the key to the abyss, and the vile altar and its servants, the "synagogue of Satan," are truly worthy of being called the entrance to hell, the ‘gates of Hades.’ The reason why demons are nourished and strengthened by sacrificial blood offered to them, and not by any bloodshed in general, lies in the contrary effect of the redeeming and binding power of the Divine Blood.

According to historians and ethnographers of the so-called ‘myth-ritual school,’ at the foundation of legends, myths, and a whole range of other pseudo-religious formations - such as magic, etiquette, games, riddles, jokes, - lies the ancient primal ritual of killing or sacrificing a divine king, a phenomenon universal to world cultures which has fallen away from belief in the True God.

In Sir James Frazer's book The Golden Bough, the ritualistic meaning of the procedure for replacing the priest at the temple of Diana of Aricia in the Nemi sanctuary, as mentioned in ancient sources, is clarified through a vast amount of historical, ethnographic, and folklore material. One could only take this position by killing the priest, who bore the title of King of the Wood. After killing his opponent, the victorious contender for the throne, usually chosen from among condemned criminals, would himself become a candidate for future assassination. Frazer shows that the custom of killing the king-priest existed in all societies at a certain stage of their development. Regicide was one of the ways of maintaining the universe in balance and was determined by the key role the ruler played in primitive society.

The Russian Orthodox historian Vladimir Mahnach, suggested that Pontius Pilate perhaps had knowledge or at least has heard of the ancient Latin tradition of ‘King Sacrifice’ on lake Nemi. Thus leading him not to be surprised by the continuous calls to execute the ‘King of the Jews’, Jesus Christ of Nazareth, whom the violent crowd were wrongly accusing of blasphemy.

‘When omens indicated that the king or the nation was in danger, the king would simulate abdication and transfer all regalia to his successor, who was supposed to take the throne’ (Ritual Theory of Myth, St. Petersburg, 2003, p. 20). This custom served as a mechanism of magical protection for the king, who was previously sacrificed in such situations.

Ethologists are aware of a particular behavior in wolf packs, which serves as an archetypal model and an organizational prototype for power relations within ancient and modern state formations. When the dominant leader of the pack ceases to bring back prey, he is culled, and his place is taken by a younger dominant male. This can be read, for example, in Rudyard Kipling's ‘Jungle Book’:

"Akela has missed," said the Panther. "They would have killed him last night, but they needed thee also" and further on:

"When a leader of the Pack has missed his kill, he is called the Dead Wolf as long as he lives, which is not long" (Kipling, ‘Jungle Book’, p. 18).

In Mesopotamia, there was a custom called šar pûhi (replacement of the king), which testified to the once-existing institution of ritualistic monarch killing.

Another confirmation of the once-practiced ritual of regicide in Babylon, according to the historians who classified themselves ‘myth-ritualists,’ was ceremonial practices such as the humiliation of the king during the New Year's carnival and the existence of a carnival king-fool (zoganes, or ‘jigana’), who was chosen temporarily from condemned criminals and killed at the end of the Zakmuk festival.

In ancient Egypt, the practice of ritual killings of monarchs is indicated by the myth of Osiris, the legend of King Bocchoris who was burned alive, the custom of Meroë, and the ritual of the Heb-Sed festival.

There are accounts from ancient authors about the custom of regicide in Meroë: "Kings are appointed from among persons distinguished for their personal beauty, or by their breeding of cattle, or for their courage, or their riches. In Meroë the priests anciently held the highest rank, and sometimes sent orders even to the king, by a messenger, to put an end to himself, when they appointed another king in his place." (Strabo XVII, 2,3).

The renowned Egyptologist Flinders Petrie believed that:

"In the wild prehistoric era, Egyptians, like many other African and Indian peoples, killed their king-priests after a set period of time to give a young king in the prime of life the opportunity to maintain the kingdom’s prosperity." However, this custom was later replaced. The "old" king, having exhausted his vitality, was deified during the Heb-Sed festival in the form of Osiris: just as Osiris died and rose from the dead, the king would die and be resurrected together with the god, with whom he was identified. In other words, according to Petrie, the main purpose of the Heb-Sed festival was the renewal of the pharaoh’s life force through death and subsequent rebirth" (Quoted in Alexey Krol, ‘Egypt of the First Pharaohs’, p. 58).

The Egyptian concept of the aging king is confirmed by ancient authors. Ammianus Marcellinus, a Roman historian of the 4th century AD, wrote about the customs of the Burgundians:

"In their country a king is called by the general name ‘Hendinos’, and, according to an ancient custom, lays down his power and is deposed, if under him the fortune of war has wavered, or the earth has denied sufficient crops; just as the Egyptians commonly blame their rulers for such occurrences." (Amm. Marc. XXVIII, 5,14).

Another cultural area providing historical material for the theory of sacrificial primal rituals is ancient Greece. "Whereas, according to existing evidence, the rituals of Egypt and Mesopotamia represent only the imitation of regicide, the traditions of Greece and less civilized peoples suggest a ritual in which the king was indeed put to death: either annually, or after a certain long period, or when his strength failed him" (Ritual Theory of Myth, p. 26).

The right of a royal son to ritually attempt to kill the king, who in the event of success would take the throne, as well as the custom of ritually strangling an aging or weakening king - explained by the necessity for the successor to capture the dying king's last breath, along with which the soul departs, in order to inherit the soul's power and might, are characteristic of the ceremonial practices of African monarchies. These customs undoubtedly show typological similarities with European regicides of the Middle Ages and Early Modern period, which concealed ancient ritualistic underpinnings behind political motives on the surface.

In his book Ritual War, Nicholas Kozlov asserts that contemporary historical and ethnographic findings, as compiled by scholars of the 'myth-ritual' school, are being reinterpreted in an effort to suppress the reemergence of the fundamentally sacred theme of ritual regicide within the public secular consciousness.

From a revisionist perspective, the assassination of a revered ruler or leader is invariably seen as a political act. The ritualistic elements of such crimes, which have caught the attention of researchers, are interpreted as deliberate political messages aimed at opponents - much like Stevenson’s pirates’ ‘black spot,’ the rotten fish of the Sicilian mafia, or the parrot eggs of the African Shilluk. By secularizing symbols of mysticism and occult practices, modern liberal and Marxist historians often obscure the deeper truths behind these events, distorting their true significance.

As one modern revisionist writes:

"The killing of a king was by no means a ritual, but simply part of political struggle. It is possible that in more ancient times, in the Shilluk and Fazogli tribes, rulers were indeed killed for ritual purposes, but by the time these tribes were studied by ethnographers, regicide had become merely an element of the struggle for power (...). Informants of Professor Evans-Pritchard claimed that a ruler could only be killed by a relative (and no one else) who sought to take his place, but this could only happen after the murder had been sanctioned by a family council, as the act itself was not considered individual but rather collective. Therefore, only those kings who provoked dissatisfaction among their relatives through their rule were sentenced to death" (Alexey Krol, p. 71).

This conclusion explains much about the circumstances surrounding the alleged ‘abdication’ and death of the last Russian emperor, Nicholas II. One cannot overlook the witty remark of a critic of ritual theory, who insists on the political nature of African regicides:

‘As we can see, the Bantu and Nilotes are no different in this regard from the French and Russians: after all, did Louis XVI and Nicholas II suffer ritual deaths?’ (Ritual Theory of Myth, p. 35).

The topic of widespread dissatisfaction, political opposition, and anti-monarchist conspiracies in aristocratic and Romanov family circles during the final years of Tsar Nicholas II's reign has been thoroughly explored by historians. These anti-Christian obsessions culminated in the murder of the Tsar’s close confidant and friend, Gregory Rasputin, with the unfortunate participation of Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich and Felix Yusupov, who was married to the Tsar's niece, and the great ‘abdication’ affair on the 2nd of March 1917.

Yet, the question of who inherited the imperial charisma of Nicholas II, a legacy made attainable by the fateful regicide on the night of July 17, 1918, remains obscured by the dominant historical narrative.

There is no way to trace the fate of the trophy or the history of veneration of this deadly relic - comparable to the Tree of the Cross, the Holy Nails, the Spear of Longinus, or Yurovsky's revolver - that is connected with the legacy of its victim. However, it is known that the bell which announced the dynastic tragedy of the Muscovite Tsardom to the people of Uglich was whipped and exiled to Tobolsk in full accordance with the ritual of taurobolium, where the instrument responsible for the sacrificial bull’s death, after a complex procedure to find the culprit, was identified and punished by flogging - the ritual axe.

The attribution of responsibility for the regicide to the ‘Russian’ Ural Regional Soviet (controlled by a group of Jews), in the minds of generations of Russians who did not participate in the revolution, serves the same purpose of legitimizing the unlawful appropriation of the Tsar's charisma by an unknown heir, as did the display of Yurovsky's ‘revolver’ as the murder weapon in the Museum of the Revolution in the early years of Bolshevik rule. This revolver stood in place of the actual instrument of ritual regicide - the four-edged stilettos, which imitated the instruments of the Divine Passion, the Holy Nails and the Spear, the marks of which were found by Nicholas Sokolov on the walls of the Ipatiev House basement.

Just as the appropriation of royal charisma is enacted through the consumption (literal or symbolic) of the flesh and blood of the murdered Tsar, so too does a portion of the Christian people inherit the imperial charisma of the royal family through their veneration and commemoration of the Tsar's sacrifice. This mystical communion in the sufferings of the holy martyrs takes place in the struggle against the lawless one.

The patriarchs and righteous ones of the Old Testament offered bloody sacrifices to God, in faith foreseeing the coming redemptive Sacrifice of the Son of God. The faith of the patriarchs, imprinted in the pure blood and testified by the silence of the innocent animals offered in sacrifice, was pleasing to God. Condescending to the weakness of the chosen people, the sacrifices offered in faith by the righteous, the Lord commanded all to offer according to the law. But from the moment the mystery of the coming Redeemer was revealed through the first sacrifices offered in faith, the devil also demanded such sacrifices for himself, making a pact with man, by which in exchange for the blood offerings dedicated to him, he promised to assist his servants in performing soul-destroying deeds - greed, fornication, and murder.

In praise of the holy martyr Cyprian, Saint Gregory the Theologian says: "Rebellious and hostile powers willingly and hastily carry out such services, seeking to increase the number of participants in their destruction. The reward for such services is sacrifices and libations, refined into vapor from blood and sacrifices adapted to the demon" (Bishop and Saint Ignatius Bryanchaninov, Ascetic Experiences, volume 3, p. 261-262).

The closest union between demonic bloodthirstiness and the magical art of demon invocation occurred in the cult of Moloch or Baal, when the ancient Israelites - God’s chosen people for preserving and observing the Divine revelation about the coming redemptive Sacrifice - fell into this idolatrous evil.

It is known that already among the lawless nations, some were stirred by demons to perform human sacrifices in order to mock the crucifixion of the Savior, which the fallen angels had foreseen.

One cannot ignore the historically relevant rituals of the enemies of Christianity and Rus, whose power flourishes in post Revolutionary Russia. For who is to say that if these ancient superstitions and worship of fallen deities (fallen angels), so common in the land of Canaan, were completely abandoned in the territories of the Pale of Settlement. This is especially important when we consider why almost the entire Romanov family, including the children, and distant relatives were ruthlessly slaughtered in the first 12 months following the ‘political takeover’.

The Book of Kings recounts the sacrifice made by the King of Moab, which he performed on the city wall in the sight of the enemy:

"Then he took his eldest son who would have reigned in his place, and offered him as a burnt offering upon the wall. And there was great indignation against Israel. So they departed from him and returned to their own land" (2 Kings 3:27)

Likewise, writes Archpriest Timothy Butkevich, the Cretan king Deucalionid Idomeneus, according to a vow made to the gods, sacrificed his own son, as the Cretans believed their god Kronos had done the same with his son for their sake (Timothy Butkevich, On the Meaning and Significance of Blood Sacrifices in the Pre-Christian World and the So-called 'Ritual Murders', Faith and Reason, November 1913, p. 288).

"During times of danger that threatened the entire state, there was even a custom of sacrificing heirs to the throne to Moloch" (Michael Palmov, ‘Idolatry Among the Ancient Jews’, St. Petersburg, 1987, p. 259).

The speculation about a ‘subterranean connection between the Ipatiev House and the Rastorguyev-Kharitonov mansion’ or other buildings on Asecnsion Hill (for example, the nearby building of the British Consulate) leads to various misleading theories about the miraculous escape of the Imperial Family, with the imitation of their execution and the subsequent disposal of the bodies of their look-alikes at Ganina Yama. This also gives rise to theories about complex burial manipulations over the Tsar’s remains, possibly serving mysterious magical purposes.

A particular historical and architectural interest lies in the underground structures of the Ascension Hill. Most of them are connected to the Rastorguyev-Kharitonov estate. The main house had deep cellars, with different sections of the house having their own autonomous hidden rooms. These were sometimes connected by passages, sometimes separate, each with its own exit. One of the cellars in the southeastern part of the building had two floors. This was confirmed by the builders who worked on the reconstruction of the house in 1936-37, after which it became the Sverdlovsk Palace of Pioneers. The builders sealed off the descent to the lower floor in the form of a spiral staircase (currently, this sealing can be seen as a concrete circle in the floor).

Underground galleries and passages led from the cellars to the park area and to the Zotov estate. It is possible that the estate's territory was connected by an underground gallery with the cellars of the Ascension Church, though this connection may have been associated with the underground structures of the ‘Commander’s Country House’, once built by Tatischev'. Passages from the cellars of the Rastorguyev-Kharitonov house spread beneath the park. The eastern part of the house, facing the park, was connected to a park gazebo-rotunda. From the rotunda, galleries branched off in two directions: toward the lake and toward the garden cellar located in the southeastern corner of the park. The main passage went from the coachman’s cellar, skirted the pond on the western side, and had an exit to the surface in the northeastern corner, adjacent to the city’s regular buildings. Fragments of this and other passages were observed during accidental collapses, park reconstructions, and pond cleanings in the late 1920s. Certain sections of the entire underground system were recorded during geophysical surveys in the 1970s. The creation of this underground system is most likely connected to the fact that Rastorguyev, Kharitonov, and Zotov belonged to the Old Believers, a group that faced religious persecution during the Russian Empire. Additionally, Old Believers tended to build underground prayer rooms, secret hermitages, and hideouts with hidden exits.

It should be noted that the underground system on the Ascension Hill has not been thoroughly studied, for example, using archaeological methods accompanied by excavations. Such research could help uncover and eventually reconstruct a unique monument of building culture and underground architecture - ‘terratecture’. Historian Anatoly Kozlov, based on archival documents, believed that there were fragments of old mining works in the depths of the Ascension Hill, in the form of short adits and shafts that appeared after the discovery of placer gold in the floodplain of the Melkovka River, with the aim of proving the primary source of the gold. The discovery of such works is unknown, but their existence is possible and could have contributed to the legend of an underground connection between the Ipatiev House and the Rastorguyev-Kharitonov mansion complex. During the construction of the new roadbed of Ascension Avenue, a significant portion of the western slope of the hill was removed, but no underground structures or old mining works were uncovered in the deep pit. A functioning underground structure, located on the eastern slope of Asension Hill, is a civil defense bunker -a series of underground rooms with corridors. The bunker has been occupied by the Russian commercial ‘Safe Bank’ since 1994. However, some reports claim that the KGB had utilized these catacombs during the later years of the USSR.

The complex architecture and terratecture of Ascension Hill strikingly corresponds to the traditions of labyrinthine funerary culture, which served the needs of the ancient Khazar cult of posthumous magical veneration of the deceased king.

‘‘The Khagan was buried in a complex structure, supposedly even under water. A large palace with twenty rooms was built for the burial, and in each room, a grave was dug. The bottom of the graves was filled with red ocher and quicklime. All these rooms were covered with golden brocade. The Khagan's body was placed in one of these rooms, and those who buried him were beheaded so that no one would know in which room he was buried’ (Michael Artamonov, Essays on the Ancient History of the Khazars, Moscow, 1936, p. 411).

According to known descriptions, the courtyard of the Ipatiev House was paved with ancient ‘stone slabs’ of a mysterious origin:

"Formerly Ascension Avenue, now Libknecht Street, leads us upward to Ascension Hill. It leads along a sidewalk, the likes of which you would scarcely find in other, even older, cities. These are wide granite slabs laid to last for centuries. Such sidewalks were one of the hallmarks of old Yekaterinburg. They have withstood the test of time and, despite street reconstructions, have been preserved in many places (as of the 1960s): on Lenin Avenue, Krasnoarmeyskaya Street, Roza Luxemburg Street, Libknecht Street, and others" (A Guide to Yekaterinburg, The City in Two Dimensions).

This stone pavement, or lithostrotos, contains a clear allusion to the Gospel narrative, giving rise to not only a mystical but also a literal interpretation of the well-known neologism ‘Yekaterinburg Golgotha.’

‘Lithostrotos – a stone pavement before the palace of the Roman procurator in Jerusalem, where judgment took place (John 19:13); elsewhere it was called a pavement laid with stones (2 Chronicles 7:3); a pavement of stones or simply a pavement (Esther 1:7); stones were laid (Song of Solomon 3:10)’ (Complete Dictionary of Church-Slavonic Language).

The stone pavement was built by Solomon in Jerusalem near the Temple. The Book of Esther tells of a stone pavement located in the royal city of Susa. According to the book Song of Solomon, the stone pavement was a necessary attribute of royal presence, the foundation of the throne, and may have indicated the capital status of the city where it was located. Compare: Red Square - the capital's square, with the meaning of the word ‘red’ (or ‘beautiful’ in Russian and Church-Slavonic) also present in the names of cities such as Kyzylorda and Kazan. It is also reflected in the name Yekaterinburg as the ‘red’ (capital) of the Urals, an expression that, in its literal sense, represents a tautology.

Max Vasmer traces the etymology of the word stol (throne) from stlat (to spread), and also compares it to the Old Indic sthalam, and neuter sthali – "elevation, hill, mainland."

Church tradition also refers to lithostrotos as the Place of the Skull, Golgotha (Mark 15:22).

On the night of the regicide, the stone slabs of the Ascension Hill were stained with royal blood. What kind of slabs were these? Neither Nametkin, nor Sergeev, nor even Sokolov thought to examine them.

Traditional cultures, which preserve the law of blood vengeance and use the desecration or defilement of enemy graves as a form of retribution, are also familiar with the custom of sprinkling the grave of a killed relative with the blood of their killer as a form of satisfaction.

This is reflected in aforementioned desecration of the Christian cemeteries reported on in 1869 (as described in Ritual Regicide: Part I), and similar situations where ‘homes’ were built on the sites of Orthodox Christian Church altars where the most important sacrifice of all - the preparation of the Holy Mysteries once took place:

'Prince Zhevakhov, who later became Bishop Ioasaph, asked Bishop Theophan about the fate of the soul of the Bishop of Belgorod, who was found hanged in the bathroom of the episcopal residence. Was his soul lost? Bishop Theophan replied that this bishop was not lost, as he did not take his own life but was hanged by demons. It turned out that the house had been remodeled, and previously it had a house church. However, irreverent builders blasphemously turned the place where the altar and the Holy Altar Table once stood into a bathroom. When sacred places are desecrated, or when murder or suicide is committed, the grace of God departs, and demons settle there. Whether the bishop was guilty of this blasphemy is hard to say, but he became a victim of the demons’ (Archbishop Averky Taushev, ‘Sacred memory of His Eminence Theophan, Archbishop of Poltava and Pereyaslav’).

One can only presume the identity of these ‘irreverent’ builders.

During the examination of the Ipatiev House by the investigative commission, abundant traces of blood were found not only on the floor and walls of the basement where the murder was committed but also in places where blood could not have reached naturally—on the doorposts, the front porch, and the outer wall of the house.

In the inspection protocol recorded by Investigator Sokolov, the following details were noted:

“On the wallpaper of this wall (separating the murder room from the sealed storeroom), in the direction of the doorpost leading to the storeroom, there are numerous blood splatters, darkened by time, but some still retain the characteristic color of blood: reddish-yellow. All of them originate from the area of the cuts (made by Investigator Sergeev), i.e., from the floor upwards and from left to right from the cuts. The shape of the splatters is distinctive, and it is clearly visible that some of them created the characteristic 'comma' shape in their trajectory as blood droplets do (…). On examining the outer wall of the house facing the garden, numerous blood droplets and splatters are observed. These droplets cover an area up to 4 arshins (an old Russian measure, 4 arshins = 284 centimeters - Д.К). They are located under the window facing the garden from the dining room, and they are directed downwards from this window and from right to left when viewed from the window into the garden. Some splatters, retaining the same direction—from the window downward and from right to left—are located under the terrace. Two large droplets are located at the very edge of the second window on the lower floor of the house, nearest to Ascension Lane, between this window and the first window on the same floor facing the lane. These droplets maintain the same form, i.e., from top to bottom and right to left, when viewed from the upper dining room window. Between the second and third windows of the lower floor, and between the third and fourth windows on the same floor, counting from Ascension Lane, are round blood stains with a diameter of 2 centimeters, as if someone had grabbed the wall of the house with bloodied fingers. All these blood spots, splatters, and stains are very pale in color, as if the blood had been diluted with water before reaching these places on the wall. The droplets and splatters begin under the dining room window facing the garden, at a distance of 1 1/1 arshins (106.6 centimeters) from the windowsill, and continue lower. The stains are located between the windows, which are almost at ground level" (Nicholas Ross, p. 320).

From the inspection protocol of the Ipatiev House conducted by Investigator Sergeev, it is evident that the floor in the room facing the garden window “bore clear traces of cleaning, in the form of wave-like and zigzag patterns from tightly adhered particles of sand and chalk (which were later determined to be traces of blood cleaning - note by Nicholas Ross). On the cornices were denser layers of the same dried mixture of sand and chalk. Opposite the inner entrance door, there is an exit to the front porch leading to the street (Ascension Lane).” In the room to the left of the inner entrance, “the floor is painted yellow, and on the left side from the entrance, there are the same traces of cleaning as on the front room’s floor. On the floor’s cornices, there is also an accumulation of dried sand and chalk mixture” (Nicholas Ross, p. 56, Protocol No. 14).

According to Old Testament and Talmudic prescriptions, the earth on which blood has been spilled must be ‘covered.’ The Jewish Encyclopedia states: “A portion of the spilled blood must be covered with earth. This is the entire requirement of Shechita, the ritual slaughtering or killing of livestock according to the Jewish rite” (The Jewish Encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron). The same applies, evidently, to human blood.

“The blood in the room where the shooting took place was 'swept into a pile,' according to Kleshchev, with a broom and thrown into the subfloor, and then the remnants were washed away with water” (Nicholas Ross, p. 285, Testimony of Anatoly Yakimov). “In the same way, i.e., with water, we washed away the blood in the yard and from the stones” (Nicholas Ross, p. 276, Testimony of Proskuryakov). “The traces of blood in the yard were swept away with sand” (Nicholas Ross, p. 110, Testimony of Mikhail Letemin).

General Diterikhs comments on the investigator and convert from Judaism, Sergeev’s oversight:

“For the establishment of the crime, he overlooks the bloodied napkins and towels, the blood-splattered wall, and does not search for the blood-soaked sawdust used to clean the floor…” (Diterikhs, p. 131).

Meanwhile, at about the same time, another “convert” from the field of science, in his sensational article for the Brockhaus and Efron encyclopedic dictionary, “The Murder of Children and the Elderly,” Sternberg draws special attention to the fact that “religious beliefs play an important role in such cases (ritual murders - Д.К) and in ethnographic societies, such as the Gilyaks, there are even categories of individuals who are buried with special honors, ‘covered’ with heaps of sacred shavings.”

It was these sacred shavings, soaked with the blood of the Royal Martyrs, which every Orthodox Christian holds sacred, that convert Sergeev did not trouble himself with ‘searching for.’ The search for bloodied sawdust certainly occupied Investigator Sokolov, as seen in the interrogation protocol of guard Philip Proskuryakov, who testified:

“Where the sawdust soaked with blood and the rags were thrown out, I don’t know” (Ross, p. 278). From Proskuryakov’s answer, it is revealed that there were also ‘rags’ in the basement, which somehow went missing.

In his “Notes on Ritual Murders,” Vladimir Dahl provides the following interesting testimony:

“In 1597, in Shidlovets, Jews sprinkled their school with the blood of a child they had tortured, which is recorded in the court books. This aligns with the Jewish ritual of anointing their doors with the blood of the Passover lamb, as well as with the above-cited testimonies on this matter by the Jewish non-commissioned officer Savitsky and the testimony of Pikulsky, who stated that Jews anoint the doors of a Christian’s house with this blood” (Blood in Beliefs and Superstitions, p. 398).

In local dialect, a ‘school’ (Schul) refers to a Jewish synagogue. During the laying and ‘consecration’ of a newly built synagogue, as evidenced by numerous historical testimonies, ritual murders of Christians, or the so-called ‘foundation sacrifice,’ are performed, requiring the sprinkling of Christian blood.

Similar traditions of ‘foundation sacrifices’ existed in the Ural region. The indigenous population of the Ural Mountains by the early 20th century had either been displaced or fully assimilated into Russian culture. According to historical sources and ethnography, human sacrifices were documented among the Voguls (Mansi) people, where victims were strangled, though these rituals occurred in remote areas far from the factories and Russian settlements.

When the Russians arrived in the Urals, they had already been Christians for centuries, but some may have brought with them a set of magical practices common in Eastern European tribes. These were mixed with some pagan customs from the Russianized and intermarried Vogs and Permyaks.

The situation changed with the rise of metallurgical plants and mines during the reign of Tsar Peter I. The mining and factory industries were critically dependent on the strength of dams and the wealth of the mines. This is where the bloody side of mountain magic became evident. According to Aleksey Ivanov’s studies, the Ural mining and factory civilization of the 18th century had sacrifice rituals deeply embedded in its cultural practices, especially human sacrifices associated with dam construction.

Russian Historian Malkov wrote that during dam repairs, the ‘living blood’ of a woman named Tomilova and two non-believing Permians, deliberately pushed into the dam's water breach, did not help prevent further issues.

Rumors suggest that during the initial construction of the dam, another man was sacrificed. To avoid harming their own, the workers selected a passing Udmurt (Votyak), captured him, and embedded his body into the dam.

A similar story comes from the village of Pakhomovo in the Ocher district. When a dam breach occurred, the locals chose a mentally disabled man named Petrunya as the sacrifice. They built a ‘deceptive’ bridge and challenged, “Whoever has courage can cross this bridge." Petrunya attempted it, and the bridge collapsed. His body, along with his horse and cart, was buried in the dam's breach. Following this, the dam reportedly never failed again.

Father Pavel Florensky recalls the abundant sacrifices made to ensure well-being during a cholera epidemic in his childhood:

"It was in the memorable year of 1892. Cholera was raging. I was nine years old then and spent the summer at my aunt's estate in Khanagya, in the Elizavetpol province. A steep road wound through the cliffs and forest to the foot of Mount Mrova. Its snowy peak pierced the sky with sharp clarity, bathed in a dark, velvety azure. Such absolute clarity, nothing blurred - a manifestation of ontology itself.

There was an ancient sanctuary where Armenians, Georgians, Tatars, and even Molokans gathered - a sanctuary that likely existed long before Christianity took root. It was the festival of Rose Vardavar: the blessing of water, drinking from a communal cup - in a cholera year! Bloody sacrifices. Blood, fat, entrails: people walked upon the entrails, and the mountain air - cold, sharp, precise, and ontological - was filled with the smell of fat and kebabs (...). This childhood impression was my inner gateway to the cult of the Jerusalem Temple (...).

And so, the altar (of the Jerusalem Temple) measured 30 by 15 cubits, or 22 by 11 arshins! An eternal fire burned upon it; this was no mere hearth but an immense conflagration, into which combustible material was continually added. Imagine the crackling, whistling, and hissing of such a fire on this altar. Imagine the near-cyclone that formed above the Temple. According to tradition, it was never extinguished by rain. But it had to be this way—what's surprising about it? They were burning entire bulls there, not to mention countless goats, rams, and more. Imagine the smell of burning flesh and fat - if the smoke from just one kebab on the streets of the East spreads for several blocks!

It’s no wonder that, in the figurative language of Jewish theology, the altar was called Ariel, the Lion of God. Indeed, it devoured both sacrifices and wood. The number of sacrifices: according to Josephus Flavius, 265,500 lambs were slaughtered for Passover. According to the Talmud, King Herod Agrippa, to calculate the number of worshippers, ordered that a kidney from each lamb be set aside - and there were 600,000. At the dedication of Solomon's Temple, 22,000 bulls and 120,000 sheep were slaughtered. At times, the priests waded ankle-deep in blood - the entire vast courtyard was flooded with it. Imagine the smell of blood, fat, and incense...”

The interest in Khazarian archaeology, largely flourishing in the early Soviet Union brought around similar insights into the mysterious religious practices of this Jewish kingdom. Soviet historians note that the cult of the ‘deceased leader-patron’ as the foundation of state-political power reached its peak during the time of the Khazar Khaganate. The Judaized ruling elite, according to tradition, considered themselves the heirs of the ten tribes of Israel that disappeared from the historical scene after the Assyrian captivity.

The state-political organization of the Khazars was based on dual governance. Real power belonged to the military king-commander, the ‘Bek’ or ‘Khagan-Bek’. The sacred ruler, who was believed to possess mysterious divine power and served as both the supreme priest and the victim of complex religious-mystical rituals, was simply known as the ‘Khagan’. He was elected from the same noble Jewish family. The Khazars associated their well-being with the person of the Khagan, and they attributed all misfortunes to the weakening of his divine power.

‘When a new Khagan was enthroned, a ritual was performed similar to the traditions of the Orkhon Turks. The king would place a silk noose around the Khagan's neck and tighten it until he began to suffocate. Then he was asked how many years he wished to reign. The half-strangled Khagan would name a number, after which, upon its expiration, he was killed…

(Michael Artamonov, Essays on the Ancient History of the Khazars, Moscow, 1936, p. 410).

In relation to non-Jews, Kabbalist Jews practice ritual acts whose magical archetype is the curse and killing of Haman, the Persian minister at the court of Artaxerxes (Book of Esther, Old Testament), which forms the essence of the holiday of Purim. The ritual aspect of this holiday consists of a collective curse and the symbolic beating of Haman by the Jews.

Describing the custom of celebrating Purim among the Jews in Tsarist Russia, the Journal Menorah, 1990 (No 2), in a rare and uncharacteristic detail for our time, describes one of the rituals of magic practiced by Talmudic Hasidim - a ritual aimed at the Russian Tsar. Among the Hasidim, one of the Jews was chosen and dressed in the costume of the Tsar. The others dressed as ministers and courtiers. Then everyone would drink, as every Jew should during Purim, and they would go to the Tzadik.

Here the actual magical ritual would begin. The Tzadik received the guests whom he would treat: ‘with great respect and behaved as one should in the presence of imperial authority.’ The Hasid, dressed as the Tsar, ‘would bulge his eyes, open his mouth often, but could barely speak a word.’ The ministers would hold him by his epaulets and sashes. Despite this, the Tzadik spoke to the guest very politely and seriously, much more seriously than one would expect from a Purim performance. He asked the Tsar to abolish the tax on meat and candles. The drunk Hasid, portraying the Tsar, 'thought about it and agreed.'

Then the Tzadik made another request: that the Tsar stop conscripting Jews into his army. 'But the previously compliant Hasid' refused. Then the Tzadik began addressing him both sternly and gently, insisting that he fulfill this request. But the Hasid remained adamant. The Tzadik began pleading, persuading, and threatening, appealing to his conscience. Other Hasidim also joined in, trying to convince the Hasid dressed as the Tsar. But he continued to refuse, repeating ‘No’, again and again.

The Tzadik became very angry and refused to see 'the stubborn Hasid' anymore that day. The next day, when the wine had worn off, the other Hasidim asked him: 'What happened to you yesterday? Why did you ignore the words of our Rebbe?' But he swore that he remembered nothing of what had happened. When they told him the events, it was all new to him, and he could not believe his ears. The command of the Tzadik was not fulfilled by the 'god' of the Hasidim. The Menorah journal concludes: 'The hearts of the Jews must turn to their Creator, and only then will the last Haman disappear.'

The identification of the Russian Tsar with Haman, the number one enemy of the Jews, whose ritual beating is the central event of Purim, has a sinister undertone. It refers to the numerous cases of ritual murders committed out of religious fanaticism, both proven and unproven in court, accusations that have loomed over fanatical Jewry for centuries. These cases form the main substance of Bolshevik revolutionary terror in Russia.

At this confusing moment in our current history we are unable to close off this investigation, as facts and analysis continues to uncover the complex narrative of occult crime which has befallen the Russian people. The suffocating darkness of despair is dispelled by an understanding that all Christians can turn to the great saintly men of Russian history in prayerful guidance.

The holy and righteous princes Boris and Gleb, Andrey Bogolyubsky, Alexander Nevsky, Tsarevichs Dmitry and Ivan, Emperors Paul I and Nicholas II - this is by no means a complete list of royal passion-bearers, heavenly leaders and protectors of the Orthodox people and the Russian state, who through Christ-like self-sacrifice affirmed the state-political and religious unity of Rus as the kingdom of the New Israel.

Worthy of attention are the prophetic words of the last Russian Emperor, Tsar Nicholas II, spoken shortly before the revolutionary upheavals that would change the centuries-old order of the Russian State. In full awareness of the hidden mystical meaning behind them, he said: "If Russia needs a sacrifice, I will be that sacrifice."

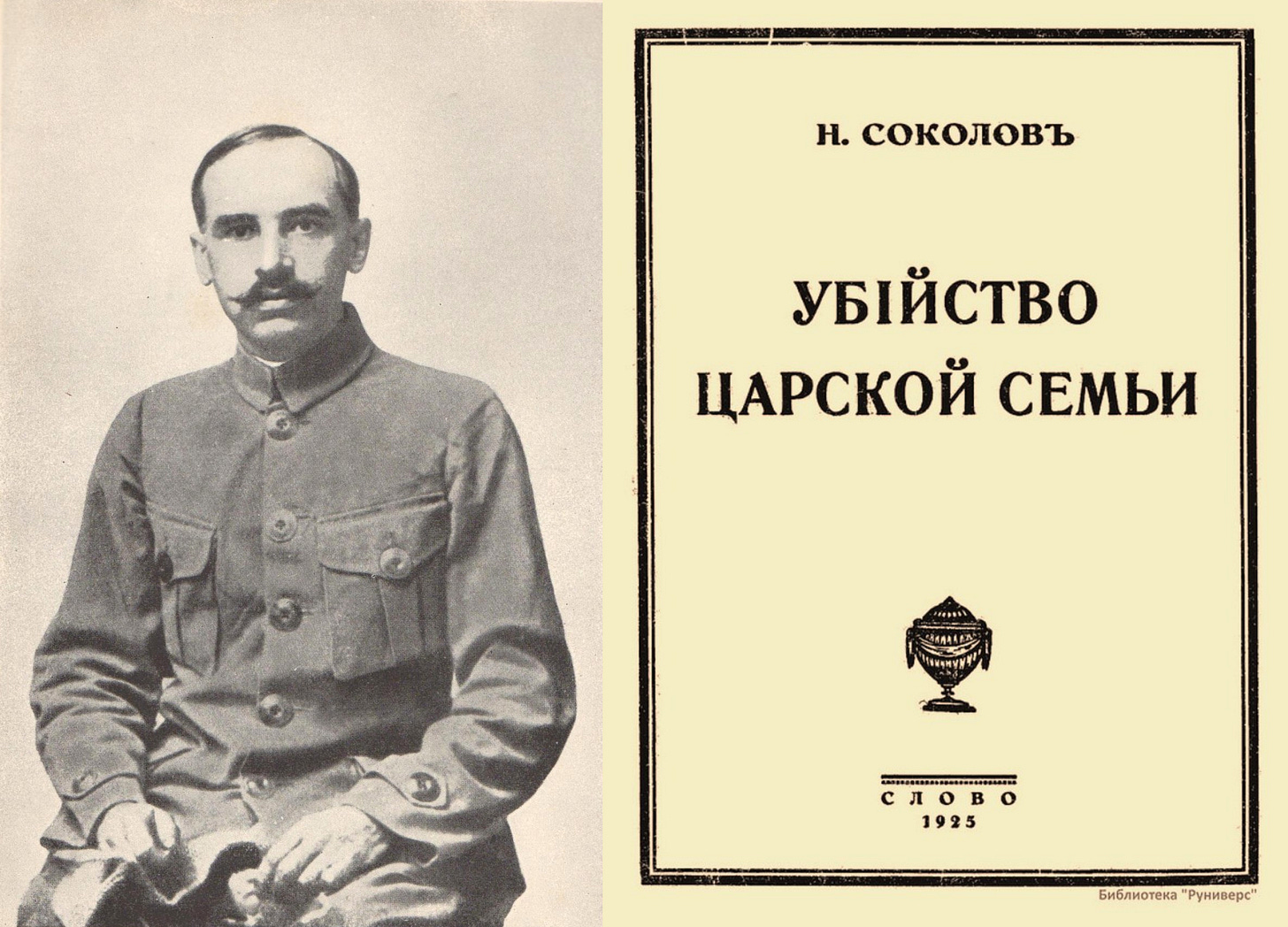

On the 10th of January 1918, Nicholas Sokolov, a prosecutor of special cases at the Penza District Court, submitted a request to resign, citing a deterioration of health.

However, the true reason lay elsewhere. According to Times Journalist Robert Wilton,

“For many years, he served as a judicial investigator in Penza. When Soviet power took hold there, he left his home and family, literally fleeing on foot to Siberia, unwilling to submit to what he called the ‘betrayers of my Motherland.’”

Another of his future colleagues, White Army Captain Peter Bulygin, described Sokolov as a young but already well-known figure in his professional circles:

“He was appointed as an investigator for major cases at the Penza District Court by Minister of Justice Shcheglovitov, who strongly supported him.”

According to Russian historians he belonged to the so-called 'Shcheglovitov’s fledglings’ a group of Russian Orthodox lawyers, that also included Boris Brazol, an associate of Henry Ford, which would later play a significant role in Sokolov’s life.

Ten days later, Sokolov left the city Penza, seeking to distance himself from the Bolsheviks who had taken over the city. His wife remained behind, and for reasons unknown, they were never able to reunite. Their marriage was blessed by the Church, and this of course brings with it significant challenges in such circumstances.

From that point onward, Sokolov would never again have a home of his own: rented rooms, railway carriages, hotels, and temporary lodgings would define his life.

His existence became one of constant movement, wholly dedicated to a single, paramount mission, as he himself expressed:

“The truth regarding the Tsar’s death is the truth about Russia’s suffering.”

The journey ahead of Sokolov was long and fraught with difficulty.

Robert Wilton wrote:

“He disguised himself as a ragged peasant and, after prolonged wanderings and adventures filled with dangers of every kind, he finally crossed the front and reached Siberia.”

Captain Peter Bulygin added:

“Sokolov arrived in Omsk disguised as a vagrant, a disguise he executed brilliantly thanks to his exceptional knowledge of the lives and ways of the common folk.”

The source of this knowledge, which enabled Sokolov not only to undertake this odyssey through Red-controlled territory but also to later investigate the murder of the Tsar and his family, was revealed by General Diterikhs in his book:

“After finishing university, as a young lawyer, he returned to the people, this time immersing himself in a different stratum of society - a criminal environment, sometimes brutal to the point of savagery. Yet, this did not repel him or make him lose love for his people. On the contrary, as a cultured, educated, and idealistic man, he saw the underlying causes of crime - ignorance and lack of culture. This deepened his attachment to the people, rooted in the quintessential Russian quality of compassion.

He developed the ability to converse with criminals, gaining their confessions and trust. He would talk to them, walk with them, live alongside them, drink tea, and smoke. Often, a hardened criminal who resisted him one day would open up, recount their story, and sometimes even weep the next. Remarkably, those he brought to justice rarely harbored resentment toward him. More often, their attitude was one of amazement, expressed in phrases like, ‘He caught me so cleverly,’ spoken with a tone of wonder rather than anger.”

'The last 40 versts (approximately 26 miles),' recounted Wilton, 'Sokolov covered with great difficulty, as his feet were completely torn and raw.'

'He was recommended to the Supreme Ruler,' recalled Captain Bulygin, 'by General Rozanov, who had known him in the past, and Admiral Kolchak trusted him.'"

The appointment of a new investigator, Nicholas Sokolov, was unlikely to alarm those concealing the murder's secret. An obscure provincial official, without connections or authority, and not even given experienced staff, posed little threat. Much more perilous to the culprit’s schemes was Admiral Kolchak's unexpected repentance. In early 1917, he had shown himself to be a republican and supporter of the February Revolution, but by early 1919, he had clearly re-evaluated events and sought to uncover the royal family's fate, despite receiving direct orders not to. Did the Admiral understand that by making such a decision, he was signing his own death warrant? Most likely, he did. Nonetheless, he did not back down, and this decision marked a significant turning point in the investigation.

The atmosphere in which the investigation into the regicide was conducted - on the eve of handing the case over to Sokolov was simply appalling.

Professor Erich Dil, from Tomsk University, who visited the Ipatiev House, was shocked:

"It was as if someone had abandoned their office, with doors wide open; anyone could come in and see or hear everything that was happening there. I noticed no security, secrecy, or discretion. (...) The inspection of the Ipatiev House left me with a very unpleasant impression. The house's security was far from adequate. Guards roamed through all the rooms; there were even instances of unauthorized individuals entering the garden adjacent to the house.

To my question about how thoroughly the house, garden, and rooms were photographed immediately after the Whites took control of them and at the beginning of the investigation, Judge Sergeev (The first Prosector in charge of the Murder case - Д.К) stated that he did not take any photographs..."

As stated prior, Admiral Kolchak's choice of Sokolov to lead the case was so fortuitous that it bordered on miraculous - few could have endured the trials Sokolov faced during the investigation.

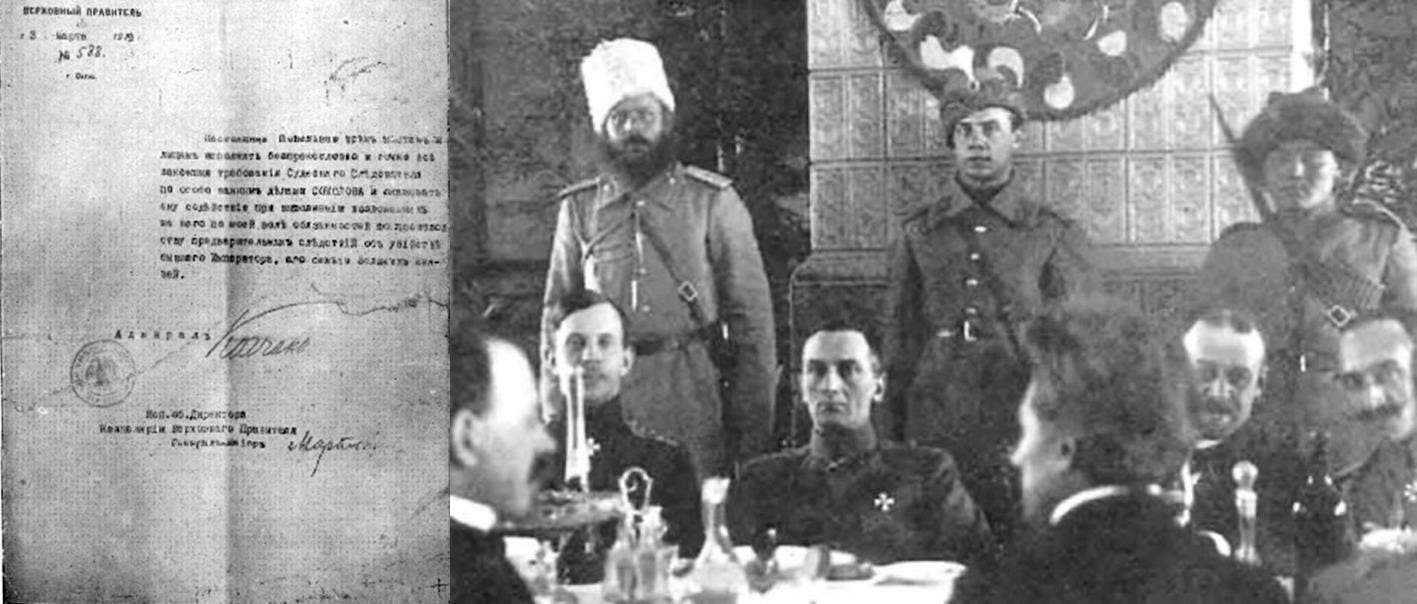

Nicholas Sokolov methodically described the sequence of events leading to his appointment to investigate the Ritual Murder case as follows:

"On 18 November 1918, supreme authority was concentrated in the hands of the Supreme Ruler, Admiral Kolchak.

On 17 January 1919, under Order No. 36, the Admiral instructed General Diterikhs, the former Commander-in-Chief of the front, to present him with all the discovered belongings of the Imperial Family and all investigative materials.

By a resolution dated 25 January 1919, Court Member Sergeev, acting under the Supreme Ruler's directive, as a special law, handed over to Diterikhs the original investigative proceedings and all material evidence.

In the early days of February, General Diterikhs delivered all the materials to the city of Omsk for the disposal of the Supreme Ruler.

The higher authority considered it dangerous to leave the case within the general category of local 'Yekaterinburg cases,' if only for strategic reasons. It seemed necessary to adopt special measures to safeguard the historical documents.

On the 5th of February the Admiral summoned me to his office. He instructed me to review the investigative materials and provide him with my thoughts on the further procedure for the investigation.

On the 6th of February the Admiral informed me that he had decided to maintain the usual procedure for the investigation and entrusted it to me.

On the 7th of February, I received an order from the Minister of Justice to conduct the preliminary investigation. On the same day, I received all the investigation records and material evidence from General Diterikhs.

On the 3rd of March, before my departure to the front (Yekaterinburg - Д.К), the Admiral deemed it necessary to secure the freedom of my actions with a special decree:

'I hereby order all authorities and individuals to comply unconditionally and precisely with all lawful demands of Judicial Investigator for Special Cases Sokolov and to provide him assistance in carrying out the duties assigned to him by my will regarding the preliminary investigation into the murder of the former Emperor, his family, and the Grand Dukes.

Signed: Admiral Kolchak.’

According to Captain Peter Bulygin, the Supreme Ruler spoke about Nicholas Sokolov very fondly saying: "I trust him; he is a man of gold."

Bulygin also recalls:

'Kolchak during the investigation in Yekaterinburg, would always summon Sokolov for detailed reports whenever he came to the front, showing interest in all the details of his work. He was particularly keen on the fate of Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich’ (The martyred younger brother of Tsar Nicholas II - Д.К).

Sokolov was deeply moved by the sincerity and simplicity of the Supreme Ruler. On one occasion in Yekaterinburg, Sokolov’s report to the admiral and their discussions about necessary measures in the investigation dragged on until four in the morning. Tired and irritable, Sokolov, in the heat of the conversation, disagreed with something the admiral said and impulsively struck him on the knee:

"What nonsense are you telling me?!"

But he immediately caught himself:

"Forgive me, Your Excellency - I lost my temper…"

Kolchak responded:

"What? Nonsense, Nicholay Alexeyevich, I didn’t even notice..."

A local Yekaterinburg banker, who rented a room to Sokolov named, Vladimir Anchikov recalls:

"He was on good terms, with the Supreme Ruler, and especially with General Diterikhs, of whom he spoke highly, saying that the general had rendered him invaluable assistance many times."

Involvement in the investigation of the regicide changed both Admiral Kolchak and General Diterikhs. General Diterikhs eventually became a convinced monarchist.

For Admiral Kolchak, this investigation revealed much, ultimately leading to his betrayal by the ‘allies’ to the Socialist-Revolutionary-Menshevik (essentially Bolshevik-aligned) ‘Political Center,’ which culminated in his execution.

It is no coincidence that Sokolov, who retained a deep sense of gratitude toward the Supreme Ruler, intended to write a book about him immediately after completing the investigation of the Tsarist case.

"I must," he said to Captain Bulygin in Paris, "begin this book as soon as I finish my current work. It is my duty to honor the memory of the Admiral..."

Many, generally hostile to the investigation of the Tsarist murders, used Sokolov's appearance to undermine confidence in his work and to present the investigation as an unserious enterprise conducted by some idle high-ranking officials.

However, wrote Mikhail Diterikhs, "Sokolov had to be understood, first and foremost, as an investigator, and secondly, as a man, a Russian man, and a patriotic nationalist."

The first aspect would become clear from the following narrative. The second requires a few words now, as it was of great significance in this case, much like an artist selecting the right colors to bring a subject closer to its true natural appearance in terms of accuracy, color, and the vividness of the light impression.

Expansive and passionate, he threw himself into any task with his whole heart, his entire being. His soul, far greater than his appearance, was eternally searching, longing for love, warmth, and idealism.

As a man with great pride and a fanatic for his profession, he often showed irritability, impulsiveness, and suspicion towards others. This was especially true in the early stages, when he first encountered people closely connected to the late Imperial Family.

Having devoted himself to this case not only as a professional and deeply Russian man but also out of exceptional loyalty to the Tsar and His family, he was inclined to see hostility in witnesses if they could not provide answers to his questions, due to his expansive nature.

A natural hunter since childhood, accustomed to the hardships of a wandering hunter's life - waiting for hours for a grouse or capercaillie in the fields, he developed extraordinary observational skills, an ability to read signs, and endless patience in pursuing his goal.

His constant interactions with the village, with peasants, nurtured in him from an early age a deep attachment to the common people, a love for all things Russian and patriarchal, as well as a profound understanding of the peasant soul, its virtues, and flaws.

As a son of a simple, honest Russian family, Sokolov was raised, grew, and matured with an unshakable belief that Russia and the Russian people "cannot live without God in Heaven and the Tsar on Earth." His education and university years only strengthened this belief. His passionate nature and love for law made him a committed monarchist by conviction. He hated Alexander Kerensky and everything associated with him to the core, referring to him only as ‘Aaronka’, due to Alexander Kerensky’s alleged Jewish ancestry.

His dislike of Kerensky was also based on professional grounds, as Kerensky had allowed jurors to join the prosecution, which, in Sokolov's view, undermined the ‘sanctum’ of the entire Russian Imperial judicial system.

Starting his investigation on 7 February 7 1919 (the ruling from the Yekaterinburg District Court came only on 24 February), Nicholas Sokolov dedicated himself exclusively to this work until his untimely death, never taking a day of rest.

Sokolov immediately approached the case seriously and professionally.

Until early March, he worked in Omsk, familiarizing himself with the case materials and questioning witnesses, including Tsarevich Alexey’s tutor, Pierre Gilliard. In September 1918, Gilliard had testified to Prosecutor Sergeev in Yekaterinburg, and from the 4th to the 6th of March 1919, he testified to Sokolov in Omsk.

After moving to Yekaterinburg, Sokolov also met with the English teacher of the Heir, Charles Sydney Gibbs, who testified to him on 1 July 1919.

In 1919, another miracle occurred, English journalist Robert Wilton arrived in Yekaterinburg. Wilton and Sokolov met and became friends, their joint efforts preventing the regicide from being buried under a shroud of lies.

Wilton’s arrival in Yekaterinburg took place after his mission in Vladivostok, when he accompanied General Mikhail Diterikhs to the Siberian city of Omsk, and then to Yekaterinburg, where Nicholas Sokolov had already relocated by that time.

Robert Wilton recalls in his book, ‘The Last Days of the Romanovs’:

"I was in Siberia on a mission; in March 1919, I met General Diterikhs in Vladivostok. (…) We had known each other for a long time from the Russian front. The general had escorted the Czech trains eastward; then he took command of the Ural Front, but intrigues forced him to leave the army. On 17 January 1919, the Supreme Ruler issued an order giving M.K. Diterikhs special authority to investigate the murder of the Imperial Family in the Urals. I became his companion and accompanied him throughout 1919, a year filled with tragic events. A month later, I was in Yekaterinburg."

It is hard to imagine what Sokolov and Wilton felt in hostile blood-soaked Yekaterinburg, the oaths they made to themselves when standing in the execution basement of the Ipatiev House, or at the hellish bonfires of Ganina Yama, and the precautions they had to take knowing that their enemies could strike at any moment. Without Sokolov, crucial evidence and investigation materials would have been lost, but Wilton actively helped gather them, and it was to the English journalist that Sokolov owed his salvation when a professional hunt began for the investigator and his materials during the retreat of Kolchak's army. Sokolov and Wilton fulfilled their duty to the end, they not only managed to extract the investigation materials but also published books that made it impossible to ignore the historical facts sorrounding of the murder in the Ipatiev House. They paid for this with their careers and lives, but it was no longer possible to silence or forget their books.

The Times journalist Robert Wilton writes:

"In the month of April, the author arrived in Yekaterinburg, where he met with Nicholas Alekseevich Sokolov, an investigating magistrate for especially important cases, to whom Supreme Ruler Kolchak had entrusted the final investigation of both the Tsar's case and all the cases of the murders of the Grand Dukes who perished in Siberia (Alapaevsk Martyrs - Д.К). The author was brought together with Sokolov by one passion that alone seemed capable enough of quickly and strongly uniting the most diverse people: hunting. I understood this man…(…) For many months, the author was in close contact with N.A. Sokolov, followed all the details of the investigation, and participated in work to which Sokolov only admitted especially trusted individuals. The inspection and examination of the site in the forest where the bodies of the Tsar and His Family were destroyed were conducted in my presence. Apart from General Diterikhs and three other people, the act drawn up by N.A. Sokolov regarding this inspection and investigation bears only the author’s signature. At N.A. Sokolov’s request, I assisted him with photographing many places and objects. I also served as a translator for the Empress’s letters in English, to which Sokolov attached great importance."

In April 1919, Investigator Sokolov discovered in the room of the Ipatiev House, where the murder of the Tsar's Family took place, an inscription in German with a distorted excerpt from a poem by Heinrich Heine, some numbers, and four incomprehensible Kabbalistic symbols. Here is what Sokolov himself wrote in the inspection report:

"On the very edge of the window sill, in black ink, three inscriptions were made one under the other with very thick lines: '24678ру year’, '1918 year,' '148467878 R,' and near them written in the same ink and the same handwriting '87 888.' At a distance of half a vershok (about 2.2 cm) from these inscriptions on the wallpaper of the wall, some signs were written with the same black lines, and had the following appearance...”

Sokolov, as a true investigator, refrained from making any hasty conclusions about this inscription and intended to begin a thorough examination of it. However, he was unable to do this in Russia due to the ongoing Civil War. The real work on studying the inscription only began during the later half of his work, and emigration in France.

After years of studious labour, in 1924, the famous book by Nicholas Sokolov, known to the Russian reader as "The Murder of the Tsar's Family," was published by the Parisian publisher Payot. However, that first book was published in French and was titled ‘The Investigation into the Murder of the Russian Imperial Family.’ In this first edition, Sokolov wrote about the mysterious inscription:

"On the same wall, I discovered an inscription consisting of four symbols and a series of numbers. Despite several interpretations, the meaning of this mysterious inscription remains hidden."

We can clearly see that Sokolov firmly linked the strange written numbers and the inscription into one whole scene, and secondly, designated the inscription ‘mysterious’.

In the Russian edition of Sokolov's book, published in 1925 Berlin by the ‘Slovo’ publishing house after the investigator's death, the above excerpt underwent significant changes. Here is how it appeared in the Russian edition: ‘On this same southern wall, I discovered a designation of four symbols.’ In the newly published 1925 Russian edition, there was no mention that these symbols were written along with numbers, nor that Sokolov considered them mysterious. It remains puzzling, as to who and for what purpose altered the text of the late Nicholas Sokolov.

From the Nicholas Sokolov protocol: "In April 1919, the Investigating Magistrate for Particularly Important Cases of the Omsk District Court N.A. Sokolov, from April 15-25, in Yekaterinburg, conducted an additional inspection of the Ipatiev House.

During the inspection, the following was found:

(...) Sealed room marked on the plan as number II, which is where the murder of His Imperial Majesty Emperor Nicholas Alexandrovich and His Family took place (...). Its appearance corresponds to the description given in Sergeev's report (page 39, volume 1).

During this inspection, the following circumstances were noted: (...)

Д. On the very edge of the windowsill, in black ink, very thickly written one beneath the other, are three inscriptions: "24 678 year," "1918," "148 467 878 R," and nearby, written in the same ink and handwriting: "87 888."

Е. At a half-span distance from these inscriptions on the wallpaper of the wall, written in the same ink and with the same black lines, are symbols, which appear as follows.

(…) The room where the murder of the August Family took place was also sealed with the same seal. (...) Judicial Investigator N. Sokolov.”

As for the essence of the matter, it was reflected in the report of Lieutenant General Mikhail Diterikhs to the Supreme Ruler Alexander Kolchak on 28 April 1919:

"To me personally, based on the study of the entirety of circumstances - those preceding the murder, the nature of the murder itself, and especially the concealment of the traces of the crime - it is entirely clear that the direction of this atrocity did not originate from the Russian mind, nor from the Russian environment. This aspect of the case grants the murder of the former Imperial Family a completely exceptional significance in terms of historical importance..."

It was to Robert Wilton, writes one of the case's researchers, historian Nicholas Ross, that ‘Admiral Kolchak entrusted the management of the photography lab that produced images for the investigation’ (Nicholas Ross, p. 569).

Prince and Roman Catholic priest, Alexander Volkonsky, the translator of the first Russian (Berlin) edition of Robert Wilton's 1923 book, evaluated Wilton’s activities during this period (p. 5):

"Finding himself in Siberia after the revolution, he was in close contact with the investigating magistrate (Nicholas Sokolov - Д.К) in the case of the Tsar's murder for many months, delving into all the details of the investigation and participating in actions to which the investigator admitted only especially trusted individuals. He inspected the room where the murder took place, was present at the inspection and investigation of the site in the forest where the bodies of the Tsar and His Family were destroyed; his signature is on the act of this inspection. He personally traced the route of the truck that transported these bodies; he took photographs of many places and objects related to the crime, and he preserved one of the copies of the investigative case, at risk to his own life."

Robert Wilton writes in that same Russian 1923 Berlin edition of his book, translated by Prince Volkonsky:

”The Reds remained in the city until July 12 (25). On the 24th, the keys to the Ipatiev House were returned to a relative of the owner, but Ipatiev himself was in the village, and the building remained empty. On the evening of the 25th, the vanguard of Czechoslovak and Cossack troops, under the command of Prince Golitsyn, occupied Yekaterinburg.”

”Meanwhile, the investigation had already been enriched with precise indications not only about the murder of the entire Tsar's Family but also about the location and method of disposing of the remains. Yet the preliminary investigation was at a standstill. Investigator Nametkin went to the Ipatiev House on the 2nd of August (1918). On August 7th, the composition of the District Court decided to transfer the case to Magistrate Sergeyev, but Nametkin still held the case until August 14th. Sergeev then proceeded with further inspection of the house…”

Here is how Robert Wilton described his first visit to the Ipatiev house, guided by Nicholas Sokolov:

"The author visited the house where the Romanovs lived and were murdered. (...) Of course, the entire house had undergone significant changes. The most basic requirements of judicial inquiry were violated. This fact alone characterizes the attitude of certain individuals towards the Tsar's case.

But the main room where the murder was committed was guarded and sealed. Sokolov led the author through the entire house and into the room of death, step by step explaining all the twists of the tragedy. He led me exactly along the path through all those rooms and staircases where the unfortunate Family went to their deaths.

In the room of death, despite the floor and walls being cleaned, clear traces of the crime remained: blood on the wallpaper in the form of numerous characteristic splashes, traces of bullet channels and bayonets. From these ominous signs and indentations, the exact picture of the brutal execution of defenseless prisoners is clearly established.

In this room, as in others, there were dirty and vile inscriptions and drawings related to rumors about Rasputin. The inscriptions were in Russian, Hebrew, German, and Hungarian. Some of them provided invaluable material for the judicial investigation."

Robert Wilton paid special attention to the unusual inscriptions found in the house, as we can read in the Berlin edition (pp. 113-114) :

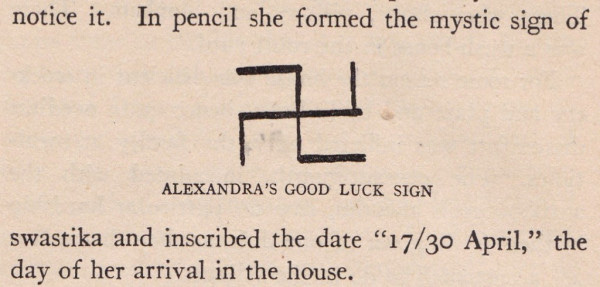

“In the room where the Empress spent her last days, upon arrival she drew a symbol of happiness, a swastika, with the date 17-30 April. Drawing this symbol upon arriving in the new room became a habit of the Empress... Alas, the happiness she invoked brought only the consolation of dying together with her loved ones. Gayda and his soldiers did not notice this inscription, somewhat hidden by a window frame, and it has been preserved.”