Ritual Regicide: The Martyrdom of the Romanovs

Part I

As many readers are likely aware, the Imperial Royal Family of Russia met their tragic end on the night of July 17, 1918. Since that time the case has remained open, with numerous crucial pieces of evidence and investigative findings, including preliminary assessments by the prosecutor, suggesting a potential ritualistic aspect to this heinous crime. While these materials can certainly stand independently, the bulk of the research has been diligently conducted and documented by historians and Orthodox Christian scholars over the past four decades. The primary authorities, whose invaluable contributions made these articles possible, include Peter Multatuli, Sergey Fomin, Yuri Vorobievsky, Nicholas Kozlov, and Leonid Bolotin. Regrettably, the majority of these esteemed authors have not published their works in English, which presents an additional challenge, necessitating translation and adding a layer of complexity to this endeavor.

References and citations are included where needed, and hyperlinks will direct readers to specific individuals, locations, and information sources. For a comprehensive understanding of the Royal Family's significance to Russia and the Orthodox Christian Church, we suggest acquiring the book 'The Romanov Royal Martyrs,' as it represents the most current and trustworthy resource available in English. These articles serve as supplementary works focusing exclusively on the ritualistic murder aspect of the martyrdom, offering separate yet relevant insights. While there exist other scholarly works, memoirs, primary and secondary sources, delving into all of them due to their extensive nature would be impractical for the average reader. If readers find the context or events perplexing, we advise bookmarking the articles, reading 'The Romanov Royal Martyrs' book for context, and then returning for a clearer understanding.

The aim of these articles is to offer a comprehensive, exhaustive, and intricate examination of regicide of the final Russian Tsar and His family in the English language.

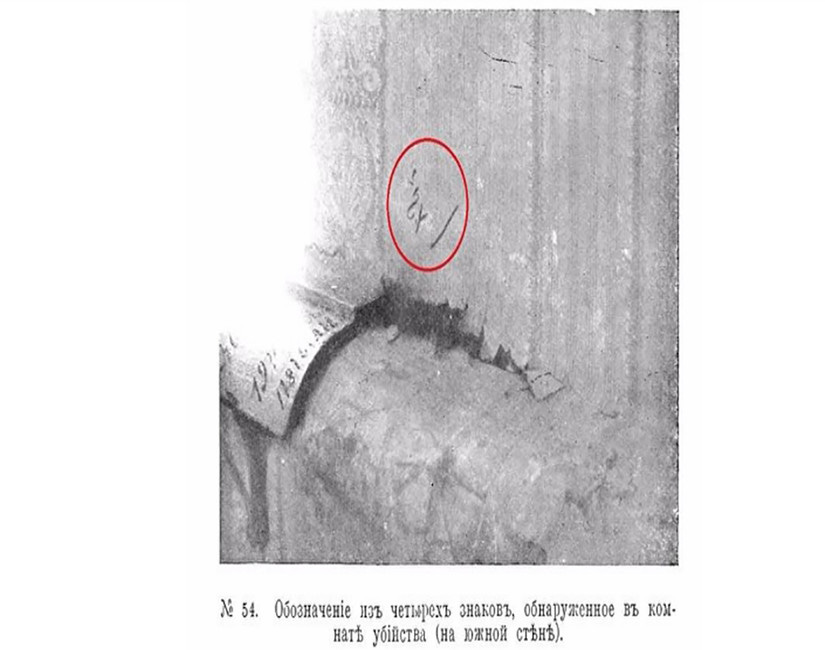

Alongside the wall, riddled with bullet holes from revolvers and nagants, stood a window bearing an inscription in a foreign tongue on its sill. Surprisingly, the inaugural investigator of the White Army, Ivan Sergeyev, overlooked it entirely, omitting it from his 1918 documentation of inscriptions, which primarily chronicled profanity and assorted graffiti adorning the walls of the Ipatiev House. Sergeyev's lineage remains somewhat obscure, save for his origin from a family of 'baptized Jews' formerly residing in the Pale of Settlement.

The inscription itself presents a curious enigma, comprising four characters reminiscent of an ancient tongue, though not as intricate as Egyptian hieroglyphs yet equally profound in essence. Can we confidently assert comprehension of the rituals entailed, not merely in the deed itself but also in its preliminary arrangements? The hints passed down through detailed documentation and interrogations weave a perplexing labyrinth rather than offering a definitive portrayal of the events unfolding during those warm days of July.

But just as in most puzzles, there is a procedure one must embark upon before the resolution becomes an inevitability. This text is that kind of work, a step in the right direction. A correctional pathway for those who find themselves among the tangled maze of historical misinformation. All stipulations and hypotheses, made either by the author, or by his predecessors, are carefully filtered through the worldview of Christianity. Without a truly Orthodox Christian vision of the present, the past remains a confusing mixture of stories and anecdotes. At worst, it becomes an agnostic mathematical endeavor, except the formulas used do not make sense, and the reader learns much, but ultimately gains nothing. Raw knowledge, whether historic or scientific, must be channeled in a useful direction. There must be a purpose to work in this realm of the past. Our purpose is to unravel one of the most explicit crimes in human history, perhaps since the unlawful murder of the Savior Himself.

A primary anchor for our investigation is the statement of Archbishop Anthony of San Francisco, successor of the venerable Saint John of Shanghai, the great miracle worker, made at the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia’s council of 1981. Archbishop Anthony was a studied, ascetic, and brave man, his courage was made evident when he spoke to his peers about the required recognition of the martyrdom of Tsar Nicholas II and his family, as well as the fact that it was not a regular political killing or execution:

‘From what has been said, it is absolutely clear that the deed was ritualistic, not a political assassination, as evidenced by the Kabbalistic inscription on the wall of the basement of the Ipatiev House, where this truly satanic crime was committed. Just as Christ was crucified for the sins of the whole world on Golgotha, forsaken by all, so the Sovereign is sacrificed for the sins of all Russia, also forsaken by all.

No one came to the aid of their Sovereign in the days of His severe trials when He was a captive of the blasphemous satanic power. The mortal sin of regicide weighs heavily over the entire Russian people, and, consequently, to some extent, over each of us. Therefore, to have even a small hope for the removal of sin from Russia, in addition to sincere repentance, it is necessary to glorify at the forefront all Russian New Martyrs – the Sovereign as the Head of the Russian State, sacrificed for the sins of the entire Russian people. Thus, the Katechon is "taken out of the way." And from this moment, we all bear witness to the unrestrained spread of evil throughout the world.’

Any act of sacrificial offering involves not only the meticulous selection of the victim and the specific rituals of its sacrifice but also a designated sacred space. While we may not possess precise details regarding the Romanovs' demise, there's no doubt about the site of their death—the Ipatiev House. If we entertain the notion of the Imperial Romanov family's murder as a ritualistic event, then the Ipatiev House assumes a sacred significance. Both communist historians and propagandists recognized symbolism in this location—the Reign of the Romanovs commenced at the Ipatiev Monastery and concluded at the Ipatiev House. However, the more one delves into the place and circumstances of their martyrdom, the more thought-provoking the puzzle becomes.

On April 6, 1918, Bolshevik leader Yakov-Aaron Moshe Sverdlov issued the directive to transfer the Tsar and his family from Tobolsk to Yekaterinburg. Sverdlov provided no rationale to the executor, Commissar Yakovlev, except for a stringent command: “Deliver the Tsar alive”. Nonetheless, given that the Bolsheviks had premeditated his murder, executing it in Tobolsk with a reliable firing squad would have been simpler than in Yekaterinburg. This implies that their demise was not merely an assassination but rather something distinct, necessitating a specific method of execution and different venue —Yekaterinburg.

One of the primary inquiries that itches the curiosity of many students of Russian history is the rationale behind selecting Yekaterinburg as the final destination and execution site for the Imperial family. The most straightforward and logical explanation posits that the city harbored a robust and militant Bolshevik party apparatus, comprising individuals well-versed in liquidations, terrorism, and unwavering loyalty to Sverdlov. However, this explanation, though succinct, warrants further elucidation. Yekaterinburg could not be classified as a revolutionary hub; it suffices to note that during the initial revolution in 1905, revolutionaries failed to orchestrate any armed uprisings or incite major disruptions. In 1918, the Bolsheviks encountered significant challenges in maintaining control over the city. One might recall the workers' uprising at the Verkh-Isetsky plant against the Bolshevik regime, the presence of the evacuated General Staff Academy housing officers who harbored evident disdain for the communists, and the plethora of 'former' individuals in the city who were targeted by the Reds in a brutal wave of terror but proved resilient to swift elimination.

In such conditions, leaving the Imperial Family in the city for several weeks seems strange. Evacuating them to the central Russian provinces would have given the Reds much greater control over the prisoners and security from any rescue attempts. It can then be safely assumed that there were reasons for Yekaterinburg to be chosen as ‘the place of keeping’ that outweighed the difficulty of maintaining the Imperial Family in the city.

The Imperial Family was brought to Yekaterinburg in the midst of the new holiday ‘May Day’, officially celebrated by the Communists as ‘Labor Day,’ which coincided with the infamous Walpurgis Night. The streets and squares of the city resounded with revolutionary songs, illuminated by numerous decorations, and theaters were packed with meetings and concerts. The sounds of May Day reached the windows of the Ipatiev House. As if in response, the Imperial Family read the Gospel daily, as it was the last week of Great Lent (Orthodox Easter fell on 5 May in 1918, just as in the year of the publication of this article, 2024). Empress Alexandra noted in her diary: "Nicholas reads the Gospel to us throughout the day." The Tsar also wrote about his reading of the Gospel: "In the mornings and evenings, I read the Holy Gospel aloud in the bedroom."

Yekaterinburg epitomized the charm of the Perm Governorate, nestling gracefully along the banks of the Iset River, where the waterway elegantly morphed into a vast reservoir, bestowing upon the cityscape an unparalleled allure. Conceived by the visionary Peter the Great as a bastion-fortress to repel incursions from the Bashkir, and christened in honor of the venerable Great-Martyr Katherine, the city held pivotal economic and martial significance. By the onset of 1914, Yekaterinburg had metamorphosed into a veritable jewel within the Urals. Aglow with the brilliance of electric illumination, adorned with stately boulevards, and graced by the spires of a dozen Orthodox churches, the city exuded a provincial charm, diverging markedly from the ambiance of Perm.

By 1918, the Yekaterinburg urban landscape was home to just over 80,000 inhabitants. The First World War wrought significant changes upon the city, especially in its demographic makeup. The crucible of factory labor, particularly at the Verkh-Isetsk industrial stronghold, provided a haven from conscription into the armed forces. As was typical, the elite of society were drawn to the front lines, leaving behind those who were more hesitant or inclined toward criminal activities, who sought refuge within the walls of factories. The collapse of the front lines brought a flood of deserters to Yekaterinburg.

Lieutenant Pierre Pascal, an emissary of the French military mission stationed in Yekaterinburg during the months of May and June 1918, rendered a vivid portrayal of the city:

‘A multitude of Austrian and even German captives. The city, more reminiscent of a hamlet, boasts several manufacturing citadels. A tapestry woven with a plethora of Chinese laborers, soldiers, and industrial workers. Devoid of creature comforts, civilian denizens, or culinary establishments or Cinemas.’

The year 1918 ushered in a climate of routine confiscations, brute force, and executions perpetrated by Bolshevik forces against the common citizenry. Moreover, Yekaterinburg found itself ensnared in the claws of unlawful criminal terror.

Simultaneously, in the capital hub of the ‘Red Urals’, the old Nikolaevskaya Academy of the General Staff harmoniously continued its work, now renamed into the Military Academy of the Worker-Peasant Red Army. In March of 1918, under the directive of Leon ‘Trotsky’ Bronstein, it made a strategic exodus from Petrograd to Yekaterinburg, marshaling around 300 erudite disciples, future officers of the Red Army. The tenure of the Academy within Yekaterinburg almost entirely overlapped temporally with the stay of the Romanov family and their tragic end.

Peter Multatuli (p. 221) gives a brief and yet contextually important description of the city:

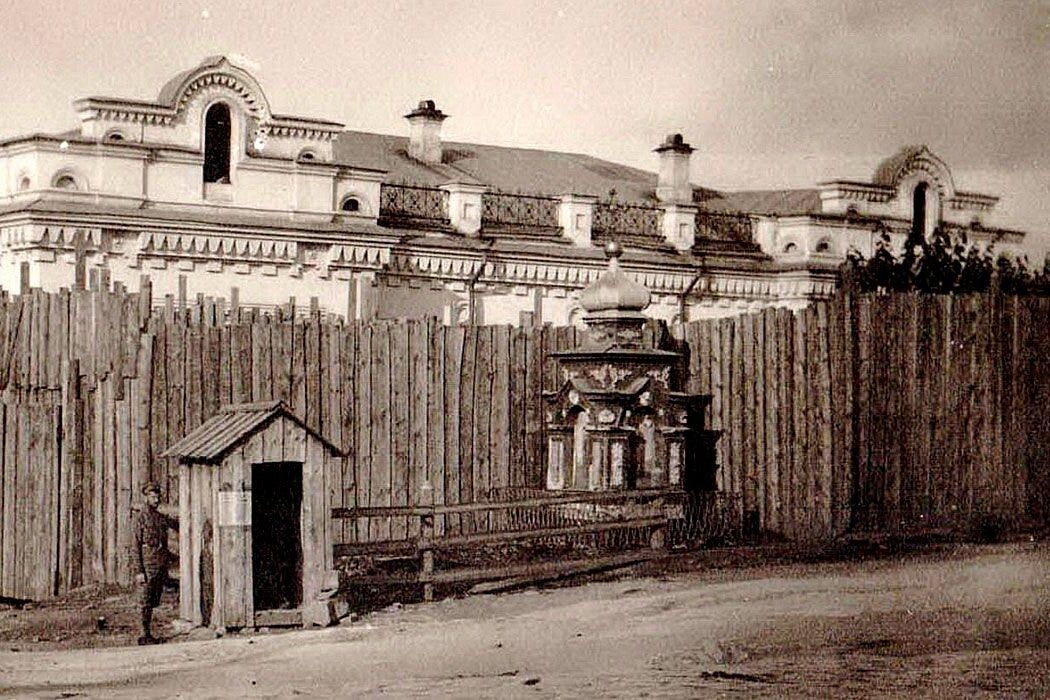

‘Yekaterinburg was a unique city, unlike other cities in the Urals. Large beautiful stone houses and even palace ensembles, such as the famous Kharitonov Palace, coexisted with small wooden houses, mansions, and shops, which with their unique beauty did not concede anything to their stone neighbors. In the city, there were two Orthodox monasteries, and the nuns of one of them, the Novo-Tikhvin Theotokos Monastery, will directly interact with the Royal Prisoners. Besides Orthodox churches, the city had one Roman Catholic church, one Old Believer church, a mosque, and a single Jewish synagogue.’

The villainy of July 17, 1918, left an indelible mark on the city. The name of the city itself was erased from the map of Russia for a long time and replaced with the name of one of the main organizers of the regicide (‘Svedlovsk’ - Д.К). In fact, along with its historical name, Yekaterinburg itself disappeared. The heavy hammer of Bolshevik dictatorship completely destroyed the unique appearance of the city. Instead of amazing small houses, estates, and mansions, monstrous gray tasteless barracks & apartments appeared.’

By the beginning of the 20th century, Yekaterinburg was under the undeniable influence of two Jewish financial clans - descendants of the ancient Khazar aristocracy - the Polyakovs (banking business) and the Günzburgs (gold industry), and through them, connected to the sphere of influence of the Rothschilds. This connection to Talmudic capital is far from accidental, as further inquiries will reveal. A renowned researcher of Khazarian history assumes the possible Semitic link of the Levant to the Urals, as he writes: ‘It is possible that during the peak of their power, their sphere of influence extended to the Ural Mountains and the Yaik River’ (T. Gotye, in the historical journal ‘New East’ (Новый Восток), 1925, No. 8-9, p. 279). This potential presence of ancient Jewish Khazars in the Southern Urals is confirmed by Alexey Schmidt in his book ‘Sacrificial Sites of the Kama-Ural Region’, wherein he states:

‘The Perm region (including the Yekaterinburg district) was within the sphere of influence of the steppe (conditionally 'Sarmatian') merchant capital (...), but of course, behind the 'Sarmatians' stood the Eastern Mediterranean, ancient, commercial capital’ (Sacrificial Sites of the Kama-Ural Region, 1932, pp. 13-15). These facts raise the real possibility that, along with the importation of goods, metals, and artifacts through the Mediterranean and up the Black Sea, there may have been a spread of very ancient Semitic and Canaanite (Hamite) religious cults.

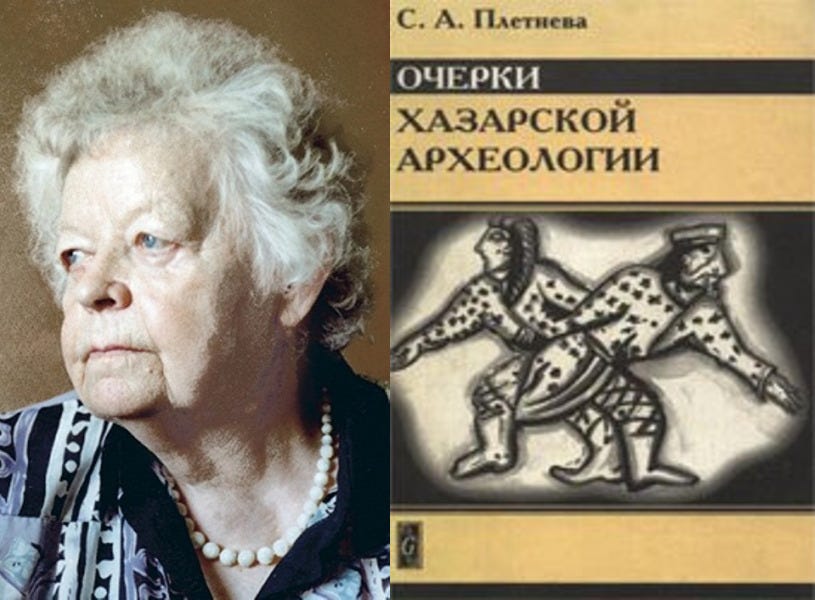

Even the most philo-semitic historians of the Soviet Union admitted that human sacrifices were common among the Khazarian people who resided on what would later be Russian Imperial territory. Professor Pletnyova writes about ‘rich male tombs’ in the land of Khazaria, many of which contained remains of young women or women with children. The women and children were seen to be slaves, concubines, the illegitimate children were probably those born from the coerced union of slave-women and their Khazar masters. Their remains were nearly always partially ‘destroyed’: ‘The common ritual was concluded by the destruction of the skeletons, sometimes completely and other times partially. Perhaps this was done as a purification ritual for him (The Khazarian master - Д.К). When not destroyed, the skeletons would always have their legs and arms thoroughly tied together’ (Svetlana Pletnyova, ‘Essays on Khazar Archeology’, p. 208-209).

Her findings about Khazarian Judeo-Pagan synthesis continue:

‘The life in Sarkel was pervaded by pagan beliefs and rituals, some of which were associated with human sacrifices…’ (p. 216).

‘In the capital of Khazaria, Sarkel, we discovered a synagogue building with signs of ritualistic oak-tree worship, and a strange grave of a dog, buried with all the dignities of a human’ (p. 214-216).

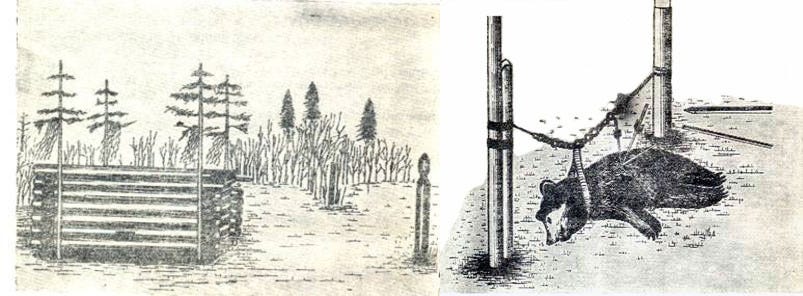

The location of imprisonment of the Royal Prisoners, first in Tobolsk and then in Yekaterinburg, was far from random. Siberia, the Volga region, the Caucasus, and especially the Urals, had already captured the attention of pre-revolutionary archaeologists who were searching for traces of ancient sacrificial cults here. ‘Where else are such vivid and rich sacrificial sites found?’, states Professor Tretyakov (Archaeological Monuments of the Urals and the Kama Region, 1940, p. 7). This conclusion seemed to be indisputable even among Soviet archaeologists.

Prior to 1735, Ascension Hill was cloaked in a dense Ural coniferous forest, devoid of any structures. In the 1760s, on the hill's western slope, where the Ipatiev House now stands, a wooden church dedicated to the Ascension of the Lord was erected at the behest of the inhabitants of Melkovskaya settlement. This church remained until 1808, built upon the remnants of an ancient 'Chud shrine.' It's worth noting that the Chud tribes were renowned for their primitive ritualistic practices, including human sacrifices. With the influx of Russian Orthodox Christians into the region, Ascension Hill swiftly transformed into the most esteemed locale in the entire city (Multatuli, 2010, p. 308).

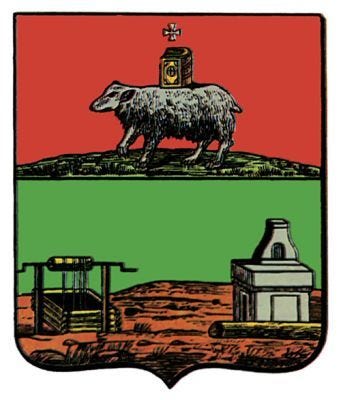

Moreover, the former Church of the Ascension, adjacent to where the Ipatiev House was subsequently constructed, stood upon a location that once served as a pagan menagerie (where sacred animals were housed by ancient tribes) or held some other connection to the worship of a wild creature. This is evidenced by both the very nomenclature of the Perm region, which linguistically traces back to a beast's name (Perm - Bern), and the crest of Yekaterinburg city, featuring a bear in the upper segment supporting the Gospel on its back, akin to an Altar table, hinting at the transformation of the pagan shrine to the One True God. Bear veneration extended beyond the Urals; for instance, in Bern, Switzerland, the bear goddess Artio was revered, and bears were confined in a cage at the central square in her honor (Sokolova, The Cult of Animals in Religions, 1998, p. 110). Another etymological interpretation of 'Perm' stems from the local Komi people, for whom it signifies 'High Place' and 'Spruce Tree Forest' (Geographical names of the Upper Kama region (With a brief toponymic dictionary), p. 133-135). The moniker 'Hypatian/Ipatiev' also translates to 'Highest' in Ancient Greek.

Basil Tatishchev, the founder of Yekaterinburg, pioneered the substantial development of Ascension Hill. Assuming leadership over the Ural mining enterprises in autumn 1734, Tatishchev erected his residence on Ascension Hill the subsequent year, fashioning it into something like a house fort. Noteworthy is the fact that towards the end of his life Tatishchev acquired negative reputation as a warlock, whether deliberately or due to misconceptions, reminiscent of his mentor and benefactor Jacob Bruce, also known as ‘Peter the Great’s sorcerer’. It is notable that post Tatishchev’s departure, the residence ceased to accommodate high-ranking dignitaries. The house boasted cutting-edge amenities for its era, including an expansive basement suited for the storage of gunpowder and armaments. Evidently, locals harbored reservations about the property and tended not to visit it often. What adds intrigue is the subsequent construction of the present stone Ascension Church on the site of Tatishchev's residence, re-purposing the sizable basement from the former mansion.

Nicholas Kozlov comes to similar conclusions as Peter Multatuli, and other historians looking into the Ascension Hill’s mysterious past, except he takes it further:

‘At the site of the Ipatiev House, where in July 1918 the Imperial Family was ritually tortured, there was a wooden church of the Ascension of the Lord (it existed until 1808) with an adjacent cemetery, built on the site of an ancient Chud shrine that once stood here. This was evidenced by a small chapel built on the site of the old church altar. In the late 19th century, this building housed a brothel, a ‘public house.’ The Ural Chud worshipped Baal, known in Russian chronicles as Veles or Volos, whose personification was a living bear.’

Near the old wooden church, there was a small cemetery, an Orthodox graveyard. After the wooden church of the Ascension, due to its dilapidation, was dismantled, a memorial chapel in the name of the Savior (or the Prophet Elijah) was built in its place. The small chapel was still clearly visible in old photographs of the Ipatiev House from the early 1900s.

According to Patristic teaching, all secret mystical sciences are considered fables, superstitious allurements, and heretical delusions. However, this does not mean that they do not have their relative elements of this world and are not organically limited by God’s Divine permission.

The significance of naming the house 'Ipatiev' has been repeatedly highlighted by numerous authors, the first of which was General Diterikhs: In 1613, within the Ipatiev Monastery, the first Tsar from the Romanov House, Michael Feodorovich, was elected to the throne, while in the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg, the last Tsar from the Romanov House, Nicholas II, met his end. Apart from this correlation, another noteworthy connection exists: the 'Ipatiev Chronicle' (or Hypatian Codex) extensively details the circumstances surrounding the assassination of 'the first Russian autocrat' - Grand-Duke Andrey Bogolyubsky. Additional insights regarding the Grand-Duke’s assassination will be unveiled towards the conclusion of this chapter.